TRENDS IN NUTRIENT LOADS FROM

THE DANUBE RIVER AND TROPHIC

STATUS OF THE BLACK SEA*

September 2006

*Extended version of a briefing note originally provided

to GEF Council on 6 June 2006

Joint Report of the GEF-UNDP Black Sea Ecosystem

Recovery Project and the GEF-UNDP Danube Regional

Project

Table of contents

Summary - the story to date ..............................................................................1

1. Introduction..................................................................................................4

2. Nutrient concentrations in the Danube River............................................4

3. Danube loads to the Black Sea...................................................................6

4. Danube flow/concentration relationships..................................................9

5. Nutrient concentrations in NW Shelf waters ...........................................11

6. Phytoplankton populations in NW Shelf waters .....................................12

6.1

Abundance and biomass .............................................................................. 13

6.2

Community composition................................................................................ 13

6.3

Chlorophyll-like substances.......................................................................... 14

7. Zooplankton ...............................................................................................17

8. Zoobenthos populations of the NW Shelf................................................17

8.1

Abundance and biomass .............................................................................. 18

8.2

Species diversity ............................................................................................ 18

8.3

Zoobenthos indices........................................................................................ 18

9. Dissolved oxygen status of NW Shelf waters .........................................20

10. Discussion..................................................................................................22

10.1 Nutrient loads and levels............................................................................... 22

10.2 Ecology, organic carbon and oxygen balance........................................... 22

Table of figures

Figure 2.1. Trends in nutrient concentrations (inorganic N and total

5

P) in the Danube River (2000-2003)

Figure 2.2. Nutrient and BOD5 content of livestock manure in the

5

Black Sea sub-basins of Romania and Bulgaria (1960-

2003)

Figure 3.1. Danube River annual nutrient/BOD5 loads and flows to

6

the Black Sea (1996-2005)

Figure 3.2.

Inorganic nitrogen load/temperature relationships at Reni

7

during 1996-1998 and 2003-2005

Figure 3.3.

Inorganic nitrogen load/temperature relationships at Reni

7

during 1996-1998 and 2003-2005

Figure 3.4.

Inorganic nitrogen loads at Reni (1996-2005), accounting

8

for flow and temperature

Figure 3.5.

Total phosphorus load/instantaneous flow relationships

8

at Reni during 1996-1998 and 2003-2005

Figure 3.6.

Total phosphorus loads at Reni (1996-2005), accounting

8

for flow

i

Figure 3.7. Danube River annual nutrient loads and flows to the

9

Black Sea (1988-2005)

Figure 3.8.

River Danube annual inorganic nitrogen land total

9

phosphorus oads (corrected for annual discharge) to the

Black Sea (1989-2005)

Figure 4.1. Time series of nutrient and BOD5 concentrations at Reni

10

(2000-2005)

Figure 4.2. Danube flow-concentration relationships for nutrients

11

and BOD5 at Reni (2000-2005)

Figure 5.1. Annual average nutrient concentrations in Black Sea

12

surface waters near Constanta, Romania (1975-2005)

Figure 5.2. Amalgamated nutrient concentration data from the

12

Romanian part of the Black Sea (1990-2004)

Figure 6.1. Phytoplankton cell density and biomass (average annual

13

data) offshore of Constanta, Romania (1983-2005)

Figure 6.2.

Long-term (1960s-2000s) average phytoplankton

13

biomass in the Black Sea: (A) annual average data

offshore of Constanta, Romania and (B) annual

September values three nautical miles offshore of Cape

Galata, Bulgaria

Figure 6.3.

Phytoplankton community composition near Constanta,

14

Romania (1986-2005)

Figure 6.4.

Chlorophyll-like substances in the Black Sea (1997-2005)

15

Figure 7.1.

Long-term summer abundance of Cladocera and

17

Copepoda three nautical miles offshore of Cape Galata,

Bulgaria (1967-2005)

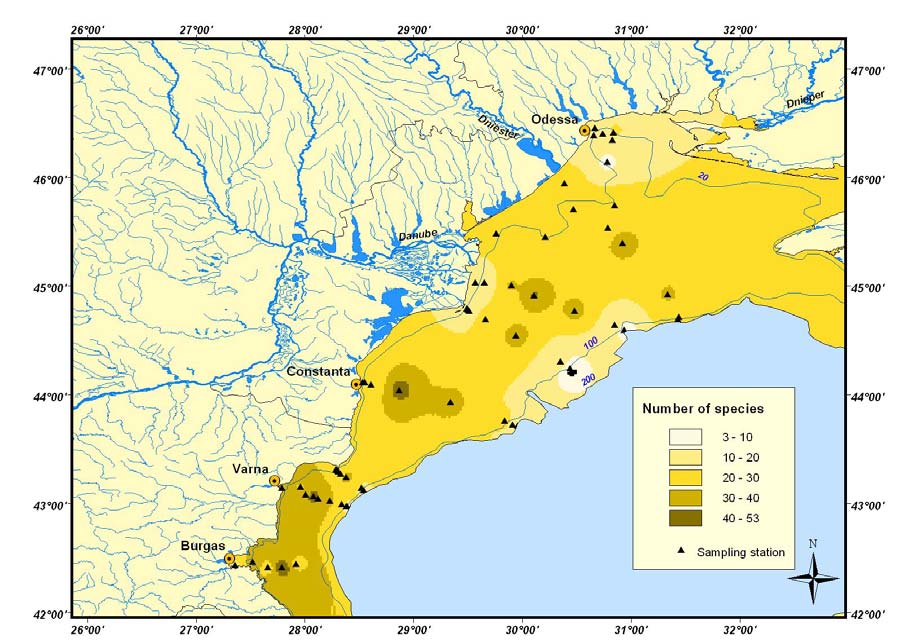

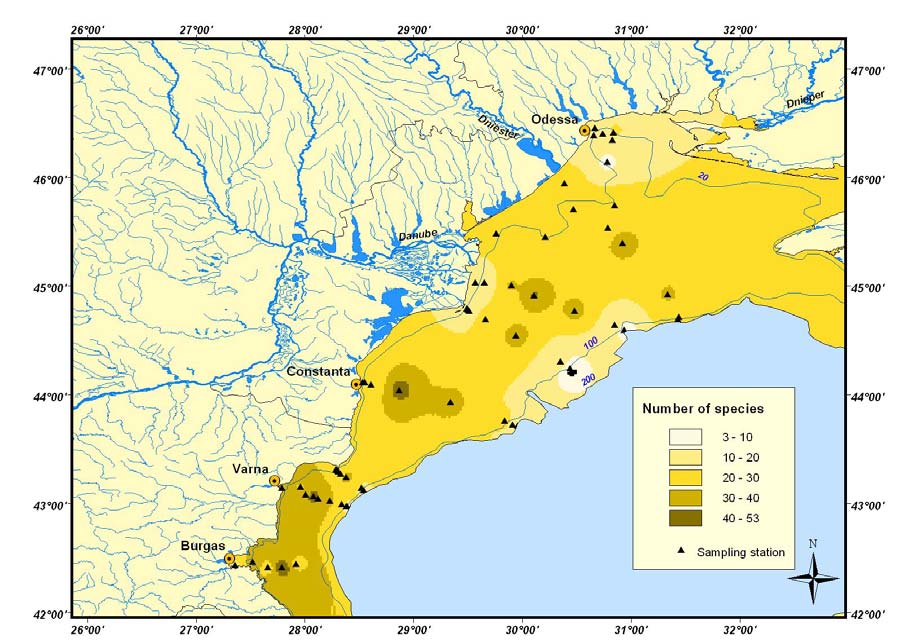

Figure 8.1

Macrozoobenthic species distribution in the NW Shelf

19

(2003)

Figure 8.2.

Number of macrozoobenthos species near Constanta,

19

Romania (1960s-2003)

Figure 8.3.

AZTI marine biotic index results - geographic

20

distribution (2003)

Figure 9.1.

Dissolved oxygen content of Romanian coastal waters

21

(1996-2004)

ii

Summary - the story to date

This briefing note brings together available data on trends in Danube River flows,

concentrations and loads to the Black Sea, in addition to an assessment of the Sea itself,

concentrating on the NW shelf where the Danube discharges. The available data are

complex, open to a range of interpretations and sometimes even contradictory1, but the

overall picture that emerges is one of a situation that is beginning to improve:

· While the emphasis of the DRP and BSERP projects has been (and remains) on

nutrient source reduction, some of the best indicators of the trophic status of the

receiving waterbody (the Black Sea and, more specifically, the North West Shelf)

are at least as closely allied to organic enrichment as they are to nutrient

enrichment (Sections 7 and 8). Further emphasis on reducing organic loading to

the Danube and the Black Sea could, therefore, contribute to improvements in the

ecological status of the Black Sea. However, no studies are known to have been

undertaken comparing the importance of riverine and coastal anthropogenic

organic carbon discharges with organic loads produced by primary production in

shallow, coastal waters.

· River loads of nitrogen and phosphorus increase with the river discharge (Figs.

3.3 and 3.5). The large variability in annual flow rates makes it difficult to

undertake statistics on short time-series of loads. The increasing trend of the

annual water volume during the past 15 years may (partly) obscure any river load

trends as a result of anthropogenic emissions (e.g. Figs. 3.2 and 3.3). Also, even

after excluding statistical "fliers" the error margin in measured nutrient

concentrations is in the region of 10-20%, a fact which may obscure (weak)

trends.

· Short-term nutrient concentration data (2000-2003) show an improving trend (i.e.

concentrations are decreasing) in the upper and middle reaches of the Danube

(Fig. 2.1). More recent (2003-2005) data suggests that this improvement is now

being reflected in reducing nitrate loads to the Black Sea (Section 3, Fig. 3.4).

· In absolute terms, there appears to have been a trend of decreasing total

phosphorus and increasing inorganic nitrogen loads between 1988 and 2005 (Fig.

3.2). However, when the trend of increasing river flow is accounted for, there is

actually a marginal decrease in inorganic nitrogen loads and a much more

substantial decrease in total phosphorus loads (Fig. 3.8). While annual flow-

corrected data over the period 1996-2001 suggest no real improvement in

inorganic N (Fig 3.4) or total P (Fig. 3.6) loads, instantaneous flow/concentration

1 For example, inorganic nitrogen loads measured at Reni as part of the Trans National Monitoring

Network (TNMN) are not consistent with data collected at Sulina (one of the three main branches of the

Danube discharging into the Sea) by the Romanian National Institute for Marine Research and

Development (NIMRD). A seven-fold decrease in the inorganic nitrogen load over a ten year period

(NIMRD data, not shown) is considered to have been extremely unlikely, and therefore the TNMN data

have been used as the basis for assessing load inputs via the Danube in this note.

1

plots (Figs. 3.3 and 3.5) indicate that progress is still being made. The large

increase in annual total phosphorus load during 2005 can be explained by the high

flows during that year (Figs 3.7 and 3.8).

· To date, the emphasis on nutrient control has focused primarily on point source

reduction. The benefits of capital investment in nutrient-stripping technology to

date have been rather small, and there is an apparent need to re-focus attention on

diffuse sources. However, the benefits of major reductions in livestock numbers

and inorganic fertilizer usage since 1988 (e.g. Fig. 2.2) almost certainly have not

yet been fully realized. When they are (and agriculture-derived nutrient loads fall

substantially), capital investment in waste water treatment plants will become

progressively more important.

· The longer-term trends in inorganic nitrogen loads, while initially appearing to be

disappointing, should be taken in context, since recent (2003-2005) data suggest

that real improvements are beginning to occur upstream (Fig. 2.1). There is a

widely acknowledged lag phase for nutrient source reduction being reflected in

reduced river concentrations and loads. There are two main reasons for this: (i) for

diffuse sources-derived nutrients, the time taken to flush historically accumulated

nutrients from soils and groundwaters to surface waters (ii) internal loading in

waterbodies (in this case referring to both the Danube and the Black Sea) from

historically-enriched sediments until new sediment-water equilibria can be

established.

· The reducing nutrient concentrations (2000-2003; Fig. 2.1) in upper and middle

reaches of the Danube suggest that this lag period may be nearing an end, a

hypothesis supported by 2003-2005 nitrate data from Reni (Fig. 3.4). The pattern

of improvements being shown first in upstream sections of the river is fully

consistent with what would be expected as the lag phase begins to end.

· Nutrient data for a coastal water site near to Constanta showed a decrease in

nitrate levels during the late 1970s, which has been maintained since (albeit with

2005 being a year of unexpectedly high concentrations, corresponding to

relatively high flows in the Danube River). Phosphate levels at the same site

showed a substantial fall during the early-mid 1990s, with a lower level being

maintained since the late 1990s (Fig. 5.1).

· The situation and trends (since 1990) in nutrient levels throughout the NW Shelf

as a whole remains unclear because of the paucity of available data, perhaps the

fairest interpretation of which is either an increase or no change in nutrient

concentrations (full data not shown). Amalgamated marine average annual

nutrient concentrations show wide variability, so timescale is critical when

assessing trends. The inclusion or exclusion of a couple of years of annual

average values could dramatically change this assessment. However, for the

Romanian part of the NW Shelf, while nitrate concentrations show an increasing

trend (1990-2004), phosphate levels have shown a decreasing trend (Fig. 5.2).

2

· Despite data suggesting that the nutrient status of the NW Shelf has not yet

improved substantially, and may even have worsened at some sites during the last

15 years, there is clear and compelling evidence of improving biological status

(Sections.6 and 7). Causes underlying this biological recovery are not fully

understood, but the most likely influencing factors are: (i) climate change; (ii)

over-fishing; and (iii) the invasive combjelly Mnemiopsis leydyi, a planktonic

organism that first appeared in the Black Sea in the early 1980s. Mnemiopsis

feeds "actively" on zooplankton and fish larvae, but only "passively" on

phytoplankton.

· Climate change could be a contributory factor in increasing nutrient

concentrations in the Black Sea, with internal loading of nutrients in the NW

Shelf appearing to be linked to wind speed, direction and duration. This may be a

direct effect of physical mixing at the sediment-water interface and/or a indirect

effect caused through changes to the dissolved oxygen status of shallow benthic

areas: at higher dissolved oxygen levels less phosphate is released from

sediments, nitrification is promoted and dentrification is inhibited. Further work

on sediment-water nutrient exchange is planned as part of the final BSERP cruise.

· Over-fishing may have resulted in decreased grazing pressure on zooplankton

and, therefore, increased grazing pressure on phytoplankton. However, available

historical commercial fishing data for the Black Sea Region are (in general terms)

sparse and incomparable. BSERP has funded a number of workshops and studies

on fish stock assessment methodologies to promote regional harmonization in the

future, but these will not help re-build historical datasets.

· Phytoplankton results strongly suggest an improving situation throughout the

1990s, and continuing improvements since then (Figs. 6.1-6.3). This conclusion is

supported by remote sensing data of chlorophyll-like substances, available since

the late 1990s (Fig. 6.4).

· The Danube continues to have an impact on zoobenthos populations just offshore

of the delta, but further north the Dniester River is almost certainly an additional

cause of disturbance to zoobenthos communities (Figs. 8.1 and 8.3). However,

zoobenthos biodiversity nears to Constanta has increased greatly since the late

1980s, suggesting that the impact of the Danube has reduced greatly (Fig. 8.2).

· Dissolved oxygen concentrations in the 1970s showed a huge deterioration in

environmental conditions/trophic status of the NW shelf in the 1970s and early

1980s. However, by the mid 1990s substantial improvements had been recorded

(Fig. 8.1). The overall situation appears to have improved further since then,

albeit with a temporary return to eutrophic conditions in 2001. A further return of

hypoxic conditions was also reported off the coast of Constanta (Romainia) and in

the Ukrainian part of the NW Shelf during 2005, but the extent and severity of

this event remains unclear (Section 8).

3

1. Introduction

During the 1970s and 1980s, the trophic status of the Black Sea, and particularly the NW

Shelf increased dramatically, resulting in extended and extensive periods of hypoxia,

with severely damaged pelagic (water column) and benthic (sediment) ecosystems. The

following short- and long-term nutrient-related targets have been agreed upon for the

recovery of the Sea:

Short-term:

to avoid exceeding loads of nutrients discharged into the Sea beyond

those that existed in 1997.

Long-term:

to reduce the loads of nutrients discharged to levels allowing Black Sea

ecosystems to recover to conditions similar to those of the 1960s.

Trophic status is determined by nutrient and organic loads/concentrations. Organic matter

in the Sea can be derived from external sources (River flows and discharges from land) or

can be generated within the sea itself via photosynthesis, predominantly by

phytoplankton, the growth of which are stimulated by elevated nutrient concentrations.

Thus, both nutrient and organic loads/concentrations need to be considered in assessing

the recovery of Black Sea ecosystems.

This briefing note provides information on indicators of Black Sea recovery, focusing on

the NW Shelf, and nutrient/organic discharges via the River Danube.

2.

Nutrient concentrations in the Danube River

Between 2000 and 2003, nutrient concentrations in the middle and upper reaches of the

River Danube showed a decreasing trend (Fig, 2.1). However at the two most

downstream sites, nutrient concentrations either showed no discernable trend or an

increase. Reasons for the difference in trends between the four most upstream sites and

two downstream sites remain unclear but must be linked to nutrient inputs from

Bulgaria/Romania, the effect of the Iron Gates Reservoirs (formed by dams across the

Danube River) and/or the release of nutrients from sediment in the lower Danube River

itself.

In the upstream reaches (above the Serbia and Montenegro/Hungary border), using

Dablas data on nutrient reduction loads generated from capital investment in Sewage

Treatment Works and comparing these with instream loads, the resultant maximum

reduction is only of the order of 7% for phosphorus and 2% for nitrogen. This suggests

that even with the huge capital investments to date, and further potential capital

investments in point source nutrient reduction in the future, little progress is likely to be

made unless inputs from diffuse sources can be effectively tackled.

However, having said this, nutrient (and organic carbon) loads from livestock (cattle,

pigs, poultry, sheep and goats) have decreased massively in many Danube/Black Sea

countries since the economic collapse of the late 1980s/early 1990s (e.g. Fig. 2.2).

Likewise, huge reductions in the use of inorganic fertilisers have also occurred (data not

shown).

4

Figure 2.1. Trends in nutrient concentrations (inorganic N and total P) in the

Danube River (2000-2003)

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database

Figure 2.2.

Nutrient and BOD5 content of livestock manure in the Black Sea sub-

basins2 of Romania (top) and Bulgaria (below), 1960-2003

) 600,000

120,000

3,000,000

e

)

e

)

n

n

e

n 400,000

n 80,000

n 2,000,000

n

(to

(to

t

o

(

l N 200,000

40,000

l P

5 1,000,000

ta

ta

D

o

o

T

0

0

T

BO

0

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

.

) 80,000

60,000

240,000

)

ne

e

)

n

e

n

180,000

n

t

on

n

40,000

30,000

(to

o 120,000

l N (

(t

a

l P

5

t

60,000

ta

D

oT

0

o

0

T

BO

0

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

1960 1970 1988 1997 2003

Data source: Dumitru, M. (2005) Romanian livestock assessment; Petkova, E. (2005) Livestock numbers

and potential nutrient/organic loads to the Black Sea from riparian countries. National report Bulgaria.

Both reports prepared under BSERP, Phase 2.

2 Land draining either directly into the Black Sea or into the Black Sea via the Danube

5

3.

Danube loads to the Black Sea

Danube loads to the Black Sea are calculated from flow and concentration data measured

at Reni, approx 30-40 km upstream of the Danube Delta (Fig. 3.1). Data from 200-2003

are officially endorsed by the ICPDR, while pre-2000 and post 2003 date are unofficial,

albeit monitored at the same site.

From these data it appears that there have not been substantial reductions in Danube-

derived nutrient or BOD5 loads to the Black Sea during the last decade. Indeed, the total

phosphorus load during 2005 (a high flow year) compared to previous years. The increase

was proportionally much greater than for ortho-phosphate, suggesting that it could largely

be explained by an increase in particulate phosphorus, concomitant with elevated

suspended solids levels/discharges (data not shown). It is interesting to note that the

ortho-phosphate and BOD5 load plots follow similar patterns, suggesting that both of

these loads are derived primarily from the same "animal" source.

Figure 3.1.

Danube River annual nutrient/BOD5 loads and flows to the Black Sea

(1996-2005)

0

60

12000

15

12000

)

a

)

)

t/3

/s

3 /s

3

10

/a)

m

(

3 t

(

m

10

0

40

8000

ad 10

8000

(

l

o

w

l

ow (

l

o

ad

e f

P

e

f

e-

g

lo

ag

N

at

r

a

e-

v

e

0

20

4000

aver

s

p

h

5

4000

i

t

r

at

u

al

h

o

a

l

a

N

-

p

u

n

n

n

A

n

r

t

h

o

A

O

0

0

0

0

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

45

12000

900

12000

)

)

/s3

/s

3

m

)

m

(

(

/a

w

)

w

t3

30

8000

l

o

a 600

8000

t/

3

l

o

10

e

f

0

(

e f

g

1

d

r

a

(

ag

loa

ad

er

v

e

l P 15

4000

l

o 300

4000

a

l

a

5

t

a

a

l

av

D

o

u

T

nnu

n

A

BO

An

0

0

0

0

8

9

0

4

5

96

97

9

9

0

01

02

03

0

0

96

97

98

99

00

01

02

03

04

05

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

20

20

20

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

20

20

20

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database; Romanian Waters National Administration.

Plot provided by Dr M. Zessner, Institute for Water Quality, Technical University of Vienna.

Temperature, reflecting seasonality, is also an influencing factor on nitrogen loads to the

Black Sea (Fig. 3.2), with an overall decrease in medium-high flow-related loads during

2003-2005 compared to 1996-1998 (Figure 3.3). When both temperature and flow are

accounted for, the beginnings of a decrease in inorganic nitrogen loads during 2003-2005

is apparent (Fig. 3.4), suggesting that the upstream trend of decreasing inorganic nitrogen

concentrations during 2000-2003 (Fig. 2.1) is beginning to follow-through to a reduction

in recent loads to the Black Sea (2003-2005).

6

For total phosphorus, as with nitrate, during 2003-5 there was a tendency towards lower

instream loads during high flow events, but at moderate flows, loads appear to have

increased when compared to the 1996-1998 situation. However, then the influence of

river flow is removed from loads, the large increase in the 2005 load at Reni (see Fig.

3.1) is effectively removed (Figure 3.6), revealing no apparent trend over the 1996-2005

period.

Figure 3.2. Inorganic nitrogen load/temperature relationships at Reni during

1996-1998 and 2003-2005

5

2004-2005

4.5

1996-1998

4

Trend 1996 - 1998

3.5

Trend 2004-2005

3

/

l

)

g 2.5

(m

R2 = 0.43

N

TI

2

R2 = 0.52

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

T (°C)

Data source: 1996-998 Trans-National Monitoring Network database; 2004-2005 Romanian Waters

National Administration. Plot provided by Dr M Zessner, Institute for Water Quality, Technical University

of Vienna.

Figure 3.3. Inorganic nitrogen load/instantaneous flow relationships at Reni

during 1996-1998 and 2003-2005

3000

2004-2005

2500

1996-1998

Trend 2004-2005

R2 = 0.66

2000

Trend 1996-1998

t

/

d)

R2 = 0.63

( 1500

N

TI

1000

500

0

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

Q (m3/s)

Data sources: 1996-1998 Trans-National Monitoring Network database; 2004-2005 Romanian Waters

National Administration. Plot provided by Dr M. Zessner, Institute for Water Quality, Technical University

of Vienna.

7

Figure 3.4.

Inorganic nitrogen loads at Reni (1996-2005), accounting for flow and

temperature

600

12000

500

10000

400

8000

a

)

t/3

0

/s)3

(1 300

6000

m

a

d

(

-

lo

MQ

I

N

T 200

TIN-load - ICPDR mehtod

4000

TIN-load, influence of Q calculative eliminated

100

2000

TIN-load, influence of Q and T calculative eliminated

Mean flow of the year

0

0

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database; Romanian Waters National Administration.

Plot provided by Dr M. Zessner, Institute for Water Quality, Technical University of Vienna.

Figure 3.5. Total phosphorus load/instantaneous flow relationships at Reni

during 1996-1998 and 2003-2005

120

2004-2005

100

1996-1998

trend 2004-2005

80

Trend 1996-1997

)

t

/

d

60

-

P (

4

PO

40

R2 = 0.13

20

R2 = 0.37

0

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

Q (m3/s)

Data source: 1996-1998 Trans-National Monitoring Network database; 2003-2005 Romanian Waters

National Administration. Plot provided by Dr. M. Zessner, Institute for Water Quality, Technical

University of Vienna.

Figure 3.6.

Total phosphorus loads at Reni (1996-2005), accounting for flow

45

12000

40

10000

35

30

)

8000

t/a

)

3

25

/s

1

0

3 m

d (

6000

20

l

oa

MQ (

TP- 15

4000

10

TP-load, ICPDR method

2000

5

TP-load, influence of high flow events excluded

mean flow of the year

0

0

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database; Romanian Waters National Administration.

Plot provided by Dr M. Zessner. Institute for Water Quality, Technical University of Vienna.

8

Over a longer period (1988-2005) the picture that emerges is of increasing inorganic

nitrogen loads and decreasing total P loads (Fig. 3.7). However if account is taken of

flows, there is actually a slight decrease in organic nitrogen loads and a much larger

decrease in phosphorus loads (Fig. 3.8). It is clear from Figs. 3.7 and 3.8 that annual

nutrient loads need to be reduced by a factor of 1.5-3 to reach the levels measured prior to

1960.

Figure 3.7. Danube River annual nutrient loads and flows to the Black Sea (1988-

2005)

1000

10000

100

10000

800

8000

80

8000

)

y

)

/s

600

6000

)

3

y

)

60

6000

/s

m

3

(

(

k

t/

k

t

/

(

m

l

P

400

4000

ta

40

4000

Flow

To

Flow

DIN (

200

2000

20

2000

0

0

0

0

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

00

01

02

03

04

05

1

959

1

988

1

989

1

990

1

991

1

992

1

993

1

994

1

995

1

996

1

997

1

998

1

999

2

000

2

001

2

002

2

003

2

004

2

005

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

20

20

20

8-

DIN kt/y TNMN/Buch.Decl.

-

1

9

5

9

19

DIN kt/y Almazow

194

P kt/y TNMN/Buch.Decl.

P kt/y Almazow

Danube discharge m3

1948

linear trend

Danube discharge m3

linear trend

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database; Romanian Waters National Administration;.

Plots provided by Dr J. van Gils, WL delft hydraulics, Delft, The Netherlands.

Figure 3.8.

River Danube annual inorganic nitrogen and total phosphorus loads

(corrected for annual discharge) to the Black Sea (1989-2005)

800

80

600

60

)

)

y

y

t/

t/

(k

(k 400

40

I

N

l

P

D

ta

o

T

200

20

0

0

9

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

5

9

88

89

9

0

9

1

92

93

96

97

9

8

99

00

01

04

0

5

198

198

199

199

199

199

199

199

199

199

199

199

200

200

200

200

200

200

-19

19

19

19

19

19

19

1

994

1

995

19

19

19

19

20

20

2

002

2

003

20

20

-195

1

948

DIN (Q corr.) kt/y

DIN kt/y Almazow

1

948

Total P (Q corr.) kt/y

Total P kt/y Almazow

linear trend

Data source: Trans-National Monitoring Network database; Romanian Waters National Administration.

Plot provided by Dr J.van Gils, WL delft hydraulics, Delft, The Netherlands and Dr. M. Zessner, Institute

for Water Quality, Technical University of Vienna.

4.

Danube flow/concentration relationships

Annual flows in the Danube show clear seasonality, with highest flows in spring.

Concentration data for 2000-2005 are plotted against flow (Fig. 4.1). Nutrients and BOD5

showed only very weak correlations with instantaneous flow, albeit that the overall

relationships were slightly positive for nutrients. Nevertheless, this is not surprising,

considering the lack of seasonality shown by all of the parameters, except for nitrate (Fig.

4.2).

9

Thus, while higher annual flows tend to results in higher loads of nutrients (nitrate and

total P; Fig. 3.1), it is only concentrations of nitrate that may substantially increase at

higher instantaneous flows (Fig.4.2). This is a surprising conclusion for total P, especially

considering the high annual total P load for 2005, corresponding to high annual flows

Figure 4.1.

Time series of nutrient and BOD5 concentrations at Reni (2000-2005)

16000

4

16000

5

.

.

l)

)

)

/s 12000

3 g/

4

/s 12000

3

m

3

g/l)

m

(

m

3 m

( 8000

2 -N

(

(

8000

t

e

w

l N

a

o

2

t

a

Flow 4000

1 itr

Fl 4000

o

N

1 T

0

0

0

0

00

01

02

03

04

05

06

00

01

02

03

04

05

06

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

16000

0.2

16000

0.4

.

.

g/l)

)

)

12000

m

/s

12000

/s

3

3

m

-

P (

m

( 8000

0.1

(

(mg/l)

t

e

8000

0.2

w

a

w

l

P

o

o

Fl 4000

ph

Fl 4000

os

Tota

h

0

0

P

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

2

0

3

0

4

0

5

0

6

0

0

0

1

0

2

0

3

0

4

0

5

0

6

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

16000

6

.

)

2

1 000

/l)

/s3

4 g

m

m

8000

(

5

ow (

2

Fl 4000

BOD

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

2

0

3

0

4

0

5

0

6

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

1/

Data source: Dr M. David, Romanian Waters National Administration

(Figs. 3.1 and 3.2), but could be a reflection of the relative contributions of point and

diffuse source-derived phosphorus to instream loads at high and low flows. However, for

nitrate the situation is more complex than such simple statements suggest, since peak

concentrations often do not occur at the same time as annual peak flows (Fig. 4.1)

thereby weakening the instantaneous flow/concentration relationship (Fig. 4.2).

10

Figure 4.2.

Danube flow-concentration relationships for nutrients and BOD5 at

Reni (2000-2005)

4

6

/

l)

g

/l)

g

4

(

m

m

2

(

-

N

t

e

l N

2

t

a

i

t

r

a

o

N

0

T

0

0

5000

10000

15000

0

5000

10000

15000

Flow (m3/s)

Flow (m3/s)

0.2

0.5

t

e

a

/l)

0.4

h

g

p

/l)

g

m

0.3

0.1

os

(

m

0.2

ph

(

l

P

P

o-

t

a

0.1

o

0

T

r

t

h

0

O

0

5000

10000

15000

0

5000

10000

15000

Flow (m3/s)

Flow (m3/s)

6

/l)

4

g

m

(5

2

D

BO

0

0

5000

10000

15000

Flow (m3/s)

Data source: Dr M. David, Romanian Waters National Administration

5.

Nutrient concentrations in NW Shelf waters

Annual average nutrient concentrations at Constanta are shown in Fig .5.1. This show a

clear trend of decreasing phosphate concentrations throughout the 1990s, with much

lower concentrations maintained through the early 2000s. The situation with nitrate is

rather different with high concentrations which occurred in the late 1970s being

maintained at substantially lower levels during the 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s,

albeit with an increase again in 2005, corresponding to elevated Danube flows (Figs. 3.1

and 3.2).

Fig. 5.2 illustrates the problems encountered when trying to amalgamate long-term data

from a range of coastal water sites, rather than using data from a single site. Here,

available data from all Romanian coastal water sites, sampled at depths shallower than

50m is shown. The overall impression is of decreasing phosphate levels and increasing

nitrate levels (as would be inferred from Fig. 5.1, over the same time period), but with

much greater inter-annual variability.

11

Figure 5.1.

Annual average nutrient concentrations in surface waters near

Constanta, Romania (1975-2005)

25

14

12

20

l

/

l

)

l

/

l

)

o

o

10

m

m

µ

µ 15

( 8

e

e (

6

at 10

itrN

4

osphat

5

h

P 2

0

0

5

0

85

90

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

995

000

197

198

19

19

1

2

2005

Data source: Dr A. Cociasu, National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta, Romania

Figure 5.2. Amalgamated nutrient concentration data from the Romanian part of

the Black Sea (1990-2004)

10

2

l

/

l

)

o

/l)

m

l

(

µ

om

t

e

a

(µ

h

N

5

1

s

p

e-at

itr

pho

N

r

t

ho-

O

0

0

90

92

94

96

98

00

02

04

90

9

2

9

4

96

9

8

00

02

0

4

19

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

19

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

Data source: National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta, Romania; BSERP

database

6.

Phytoplankton populations in NW Shelf waters

Phytoplankton data can be considered both in terms of major taxonomic groups and in

terms of cell density and biomass-related factors. Of the latter two, biomass is the more

important indicator, because of the large variability in size between different species and

the fact that phytoplankton community composition changes on a seasonal basis.

Biomass is estimated from cell volume (biovolume) measurements. Chlorophyll-a is a

pigment present in all photosynthetic phytoplankton, typically comprising 1-2% of dry

weight, that is used as a surrogate of biomass. Remote sensing (satellite imagery) data

can be used to monitor chlorophyll-like substances in large waterbodies, and this also is

used as a surrogate of phytoplankton biomass. However, because different taxonomic

groups also contain a mix of other types of chlorophyll (-b and c) and additional

photosynthetic pigments, even though the remote sensing images are calibrated against

measured chlorophyll-a concentrations, there is some margin of error. Thus, the images

can over- or under-estimate actual data, depending on what species are present, at

different times of the year and in different areas of the sea. Remote sensing images are,

therefore, a less reliable indicator of phytoplankton biomass than chlorophyll-a

measurements.

12

6.1

Abundance and biomass

Phytoplankton cell density and biomass have shown considerable inter-annual variability

over the last two decades (Fig. 6.1). In 2001, when a temporary return of hypoxic

conditions was observed an increase in cell density occurred equivalent to that observed

in the 1980s. However, when longer-term averages are considered, an emerging pattern

of reducing plankton biomass can be seen, albeit with average levels observed in the last

3 years (2003-2005) at Constanta being typical of those occurring in the 1960s (see Fig.

6.2). Results from Cape Galata, while not as promising as those from Constanta, still

show a trend in the right direction, with average phytoplankton biomass levels during

1998-2005 being nearly half of those measured during the 1980s.

Figure 6.1.

Phytoplankton cell density and biomass (average annual data)

offshore of Constanta, Romania (1983-2005)

Data source: Dr A. Cociasu, National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta, Romania

Figure 6.2. Long-term (1960s-2000s) average phytoplankton biomass: (A) annual

average data offshore of Constanta, Romania and (B) annual

September values from three nautical miles offshore of Cape Galata,

Bulgaria

9

9

(A)

(B)

)

)

3

3

m

/m 6

6

g/

m

s (

a

s

s

(g

m

as

3

i

o

3

B

i

om

B

0

0

s

3-

0

1-

0

1-

5

-

3

-

0

-

7

-

5

1960

198

199

199

200

200

200

1961

196

1983

199

1995

199

1998

200

Data source: (A) Dr L. Boicenco, National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta,

Romania; (B) Dr S. Moncheva, Institute of Oceanology Bulgarian Academy of Science, Varna, Bulgaria.

6.2 Community

composition

The ratio between major phytoplankton taxonomic groups can also be used as an

indicator of ecosystem status. As with phytoplankton biomass/abundance data there is

considerable inter-annual variability. Nevertheless, grouping data from longer periods of

time together, once again indicates that recovery is once again taking place (Fig. 6.3).

13

Unfortunately, taxonomic data are not available from the 1960s reference period, but it is

clear that in terms of the contribution of major taxonomic groups to total phytoplankton

biomass, at least, the situation in recent years has returned to a situation resembling that

in the 1980s. Post-2000, the situation with regard to cell counts has been rather less

straightforward, since the temporary return of eutrophic conditions in 2001 was reflected

very severely in the phytoplankton population, with almost 100% of phytoplankton cell

counts in the following year consisting of "other" groups (data not shown).

Figure 6.3.

Phytoplankton community composition near Constanta, Romania

(1986-2005)

100%

100%

80%

80%

60%

60%

40%

40%

20%

20%

0%

0%

6-

1-

1-

86-

90

91-

00

01-

05

90

00

05

19

19

19

20

20

20

198

19

199

20

200

20

Other groups density

Other groups biomass

Dinoflagellate density

Dinoflagellate biomass

Diatom density

Diatom biomass

Data source: Dr L. Boicenco, National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta,

Romania

6.3 Chlorophyll-like

substances

Figure 6.4 shows remote-sensing images of the Black Sea, obtained using Seawifs

satellite data. Although there is considerable monthly and yearly variability in the data,

high chlorophyll levels were clearly evident in 2001, notably during the period May to

September, confirming the temporary return of eutrophic conditions at this time.

However, during 2003, levels of chlorophyll-like substances appeared to be very low,

particularly along the NW coastline where the Danube discharges into the Sea. Overall,

there appears to have been lower chlorophyll levels in the Black Sea since 2001 than in

previous years. November 2004 is particularly noticeable because of the dominance of

blue colours, indicating considerably reduced chlorophyll levels (and therefore

phytoplankton biomass) compared to the same month in previous years.

14

Figure 6.4.

Chlorophyll-like substances in the Black Sea (1997-2005)

Januar

y

Marc

h

May

Jul

y

Septembe

r

November

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

15

Figure 6.4

Continued...

Januar

y

March

May

Jul

y

Septembe

r

November

2002

2003

2004

2005

Data source: http://marine.jrc.cec.eu.int/frames/archive_seawifs.htm

16

7. Zooplankton

Microzooplankton in the Black Sea are dominated by Cladocera and Copepoda, long-

term data for which present a fascinating reflection of the biological changes that have

occurred since the 1960s. Fig. 7.1 shows a clear long-term trend of declining abundance,

with extrapolation of the long-term linear regression line suggesting that in 2006,

zooplankton abundance would be a full order of magnitude lower than that in 1967.

However, there is a great deal of inter-annual variability in the figures, and when only

more recent data are considered (e.g. a trend line for data from 1997-2005 is shown in Fig

7.1), these suggest that zooplankton abundance has actually levelled off or increased over

the last decade.

Figure 7.1

Long-term summer abundance of Cladocera and Copepoda three

nautical miles offshore of Cape Galata, Bulgaria (1967-2005)

5

r

/

l

)

be

4

num

e

(

nc

nda 3

1967-2005 data set

u

b

1997-2005 data set

a

Linear (1967-2005 data set)

g10

lo

Linear (1997-2005 data set)

2

966

972

980

986

996

002

1

1

1

1

1

2

Data source: 1967-1994, Prof. A. Konsulov, 1994-2002, Dr. L. Kamburska; 2003-2005, Dr K Stefanova,

IO-BAS. All data provided by Dr Stefanova, Institute of Oceanology Bulgarian Academy of Sciences,

Varna.

8.

Zoobenthos populations of the NW Shelf

The status of zoobenthos (sediment invertebrates) communities can be assessed using a

range of reporting metrics:

· Abundance (the total number of all species per m2 of sediment)

· Biomass (the total number of individual invertebrates (of all species) per m2 of

sediment

· Number of species present (the total number of species present at any one site)

· Zoobenthos indices

Sampled were collected during one of the Phase I BSERP research cruises (2003), and it

is intended to re-sample these sites in the Phase II cruises during 2006 for comparative

purposes to see whether/how the situation has changed

17

8.1

Abundance and biomass

A large area of increased abundance/biomass was present in front of the Danube delta

and Constanta (Romania), with decreased abundance in front of Odessa (Ukraine) -

possibly due to contamination by pesticides and at more southerly Bulgarian sites.

Abundance/biomass clearly decreases offshore. The pattern of decreasing

abundance/biomass in southerly waters is due to the reduced influence of major rivers

(the Danube and Dniester) which provide an import source of nutrients and organic

carbon which are cycled through the food chain.

8.2 Species

diversity

The higher species richness in shallower waters (Fig. 8.1) is associated with good

dissolved oxygen conditions. The observed lower diversity in deeper areas was fully

expected due to natural oxygen depletion with increasing depth in the Black Sea. (e.g.

Fig. 8.1). In the shallow Danube delta and Odessa areas low benthic diversity is

preconditioned by the highest content of silt/clay fraction in sediments and aggravated by

the decreased oxygen concentration associated with anthropogenic eutrophication. The

effect of toxic substances may also play a role in the Odessa area (data not shown).

While the 2003 data provide a good snapshot of zoobenthos biodiversity, an example of

trends in biodiversity is given in Fig 8.2. Here, the improving situation can be seen

clearly the number of species has doubled since the mid-1990s, albeit with some way to

go before the "reference" situation of the1960s can be re-established.

8.3 Zoobenthos

indices

A range of zoobenthos indices exist for report purposes. Fig 8.3 shows results for the NW

Shelf using the AZTI Marine Biotic Index (AMBI) one which provides rather

optimistic results compared to other zoobenthos indices:

· The Bulgarian coastal area is distinguished by good, occasionally high zoobenthic

status.

· The Danube plume area is characterised by moderate to poor zoobenthic status,

although improving status is evident in more southerly Romanian wasters (with

increasing distance from the Danube).

· The Dniester area coastal stations are moderately disturbed with an improving

situation offshore.

· The AMBI results for most Odessa area stations (only slightly disturbed)

contradict those of other zoobenthic indicators (lowest abundance of crustaceans,

lowest species richness, absence of adult molluscs, etc.).

· Deep area stations are generally considered to be undisturbed.

18

Figure 8.1.

Macrozoobenthic species distribution in the NW Shelf (2003)

Data source: Todorova, V and Konsulova, T., IO-BAS (2006) Ecological state assessment of zoobenthic

communities on the North-Western Black Sea Shelf the performance of multivariate and univariate

approaches. Presentation made at the Black Sea Scientific Conference, 8-10 May 2006, Istanbul.

Figure 8.2.

Number of macrozoobenthos species near Constanta, Romania

(1960s-2003)

60

a

x

a

40

f

T

e

r

o

b 20

m

u

N

0

60s

19

1

988

1

996

1

998

1

999

2

000

2

001

2

002

2

003

Data source: Dr C. Dumitrache, National Institute for Marine Research and Development, Constanta,

Romania

19

Figure 8.3.

AZTI marine biotic index results - geographic distribution (2003)

Data source: Todorova, V and Konsulova, T. (2006) Ecological state assessment of zoobenthic

communities on the North-Western Black Sea Shelf the performance of multivariate and univariate

approaches. Presentation made at the Black Sea Scientific Conference, 8-10 May 2006, Istanbul

9.

Dissolved oxygen status of NW Shelf waters

Between the early 1970s and early-mid 1980s, the area of the NW shelf affected by low

dissolved oxygen conditions (hypoxia) increased in size (data not shown). However, by

the mid 1990s the situation was beginning to recover and had improved further by 1999

(Fig. 9.1).

A return of hypoxic conditions in 2001 was clearly recorded in mussel population age

structure statistics (mussels form annual growth rings, similar to trees). Thus, samples

collected from coastal waters between the Danube delta and Odessa (Ukraine) regions (at

25 m depth) during 2003 contained very few older (>2 years) mussels, since these has

died during the 2001 event (data not shown).

Fig. 9.1 reveals that while DO levels fell substantially in Romanian coastal during

summer 2001, the overall trend since 1996 has been one of improving status. A transient

hypoxic event occurred close to Constanta in summer, 2005, resulting in a fishkill. While,

the affected area appears to have been highly localized within Romanian coastal waters, a

hypoxic event was also reported in the Ukrainian part of the NW Shelf during summer of

the same year.

20

Dissolved oxygen measurements taken just above the sediment should be one of the best

indicators of trophic status. However, robust data are very expensive to collect. In reality,

such monitoring needs to be continuous (e.g. measurements taken every 30 minutes to

account for diurnal fluctuations in dissolved oxygen levels), with very good spatial

resolution. Manual monitoring is, therefore, not pragmatic. Thus, a network of buoy-

mounted sondes/probes is required to produce robust data, with regular (perhaps

fortnightly) servicing/re-calibration of the instruments, rather than the series of snapshot

values illustrated in Fig. 9.1. Clearly this is not possible, given the current financial

restraints. A single day of hypoxia will strongly affect zoobenthos populations for years

in the future.

Figure 9.1.

Dissolved oxygen content of Romanian coastal waters (1996-2004)

Oxygen saturation at bottom of WBS

station Sf. Georghe

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

O

distance to coast: 6km

x

y

distance to coast: 18km

g

20

e

distance to coast: 30km

n

s

a

0

tu

r

a

t

i

o

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

n

[%

]

Oxygen saturation at bottom of WBS

station Zaton

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

distance to coast: 10km

O

distance to coast: 14km

x

y

distance to coast: 24km

gen

20

distance to coast: 32km

sa

0

t

u

r

a

ti

on

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

[

%

]

Oxygen saturation at bottom of WBS

station Constanta

140

120

100

80

60

distance to coast: 2km

40

distance to coast: 12km

O

distance to coast: 22km

xyg

20

distance to coast: 46km

distance to coast: 70km

e

n

sa

0

t

u

r

a

t

i

o

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

n

[

%

Data source:

]

Cociasu et al. (2003-2005) Deliverables: D7.1 Romanian report; D7.3 Romanian annual

reports 2001-2002; and D7.6 "Summary report on field and laboratory work in 2001-2003 in comparison

with previous observations in the Western Black Sea" from the project "Nutrient Management in the

Danube Basin and its impact on the Black Sea" supported under contract EVK1-CT-2000-000 of the 5th EU

Framework Programme, http://danubs.tuwien.ac.at

21

10. Discussion

10.1

Nutrient loads and levels

As discussed in Section 5, there is a paucity of data to illustrate trends in nutrient

concentrations within the NW shelf as a whole, though there is one particularly useful

dataset from Romanian waters, albeit likely to be influenced to a large extent by changing

local nutrient loads from land. NIMRD data (not shown) suggest a major decrease in

nutrient levels at Sulina, close to where the Danube discharges into the Black Sea, but

this is a coastal site which again is likely to reflect changes in local nutrient discharges

from land. The extent of the decrease in nutrient levels at this site certainly cannot be

explained by the relatively small decreases in Danube loads observed at Reni, particularly

with regard to nitrate, since about half of the flow in the Danube is groundwaterderived,

with available groundwater nitrate data (not shown) failing to show a major decrease in

concentration.

Fixed nitrogen (organic and inorganic) applied to land as fertiliser (including livestock

manure) is more rapidly exported to rivers/sea in surface runoff than via groundwater.

(Groundwater is a relatively unimportant supply route of phosphorus to surface waters.)

So, in the years following the economic collapse of the late-80s-early 90s when regional

livestock numbers and inorganic fertiliser sales rapidly declined, it is possible that

nutrient loads to the sea via surface water runoff/soil erosion) did decline substantially,

but data to support, such a theory is mixed. Certainly, data from Reni show flow-

corrected inorganic nitrogen loads from the Danube hardly to have changed since 1988;

but the trend in total phosphorus loads is very different, illustrating an obvious decrease

since 1998, and with a particularly rapid fall in 1992/1993 compared to previous years.

Much greater success has been achieved with reducing phosphorus than inorganic

nitrogen loads to the Black Sea. This success appears primarily to have been the result of

reducing phosphate loads to land as both inorganic fertiliser and as livestock manure.

However, in many countries a shift away from intensive livestock units to more extensive

livestock production techniques has almost certainly contributed to the long-term trend.

10.2

Ecology, organic carbon and oxygen balance

The microzooplankton results (Section 7) suggest that a huge change in Black Sea

ecology has occurred since the late 1960s, and it would be almost impossible to argue

otherwise. However, the trend is in the opposite direction to that which would be

expected if eutrophication was the only environmental problem, since higher nutrient

levels typically result in higher abundance and biomass of phytoplankton, zooplankton

and higher predators; not a 10-fold decrease, as Fig. 7.1 could suggest. Clearly, then, the

zooplankton results need to be viewed in the light of wider environmental issues:

The phytoplankton results (Section 6) are very interesting. Biomass levels have been on

a downwards trend since the worst eutrophic period of the 1980s, as would be expected if

nutrient levels within the Sea had fallen. Supporting evidence for the downwards trend in

phytoplankton biomass levels in the whole of the Black Sea (not just two sites, relatively

close to land) is provided by remote sensing images (Fig. 6.4).

22

Recent unpublished data from the BSERP July/Sept 2006 research cruise suggests that

along a transect within 15-20 miles of the Dniester River mouth, organic loading and

inefficient cycling of organic matter still allow hypoxic conditions to occur. This cruise

also found Noctiluca3, a heterotrophic phytoplankter to be present in large densities at the

outer edge of influence of the Danube inflow. Noctiluca is recognized as an indicator of

eutrophic conditions in the Black Sea, and a gradual shift towards non-photosynthetic

phytoplankton (Noctiluca and other taxa) could help explain, in part at least, the observed

trend of decreasing chlorophyll levels. Fig 6.3, while not including data for the 1960s,

still demonstrates the huge changes that have taken place in major phytoplankton

taxonomic groups, since the phytoplankton community during this period was dominated

completely by dinoflagellates and diatoms.

Over-fishing is still considered one of the most important environmental problems facing

the Black Sea. It doesn't matter whether a relative reduction in the abundance/biomass of

top-level predators (e.g. horse mackerel) or lower level consumers is the consequence,

the result is reduced grazing pressure on zooplankton, and therefore an increase in

grazing pressure on phytoplankton. Fig. 6.4, showing a trend of decreasing levels of

chlorophyll-like substance, supports the theory that zooplankton grazing pressure has

increased since 1997. However changing chlorophyll levels can also be interpreted in

another way: that zooplankton levels mirror the "carrying capacity" of the sea for

phytoplankton, so reducing chlorophyll levels (as an indicator of phytoplankton biomass)

would be expected to result in lower zooplankton biomass. Unfortunately,

microzooplankton biomass data are not available, only abundance data.

Mnemiopsis leidyi. This fast-reproducing comb jelly was first identified in the Black Sea

during the early 1980s and its impact on native biota and fisheries has been devastating.

By the mid 1990s, estimates of its total biomass in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov

approached 1 billion tonnes. Mnemiopsis actively feeds on fish larvae and zooplankton,

but only passively on phytoplankton. The issue here is the relative feeding pressure

Mnemiopsis exerts on fish larvae compared to zooplankton, which is not fully

understood. Certainly the downwards trend in cladocerans and copepods (Fig. 7.1) started

a long time before Mnemiopsis was first identified in the Sea. Now that a major predator

of Mnemiopsis (another invasive comb jelly, Beroe ovata) is abundant in the Black Sea,

increasing in numbers since the mid-1990s, this could have helped microzooplankton

populations to recover to higher levels than those observed in the 1990s.

The overall picture that emerges of ecology is one of recovery. However, the presence of

alien species may have had a greater and more long-term impact than previously thought.

There is evidence of a new "type" of ecosystem having established in the NW Shelf at

least, leading some experts to consider that a full return to 1960s ecological conditions

may prove to be even more challenging than originally thought, despite further planned

reductions in nutrient loads.

3 Noctiluca enumeration is undertaken as part of microzooplankton monitoring, because of the relatively

large size of this dinoflagellate genus (typically 400-600 µm).

23

Document Outline